Ask MPS

Post date: 14/04/2015 | Time to read article: 5 minsThe information within this article was correct at the time of publishing. Last updated 18/05/2020

Miss Francesca Th’ng and Mr Marios Patronis share the case of Mrs A, who sadly died following the insertion of a chest drain after surgery

Case snapshot

- Mrs A was admitted for pleural effusions after cardiac surgery

- Chest drain inserted was later found to be in her abdomen

- Laparotomy revealed perforated diaphragm and liver injury

- Mrs A passed away several days later

- Past medical history of spinal operation felt to have contributed to Mrs A’s outcome

- It is important to study any patient’s past medical history on initial assessment, even if it initially seems unrelated

- Be mindful of all possible adverse outcomes, especially when carrying out invasive procedures.

Facts

- Chest drains are widely used throughout the medical, surgical and critical care specialties

- Chest drains are inserted to drain pleural collections in acute and elective settings

- Statistics suggest that 64% of patients, who have chest drains inserted, have no adverse effects, 1% have the outcome of death (NPSA, 2008)1

- Pre-drainage risk assessment includes checking coagulation status, considering other respiratory pathology, as a differential diagnosis and checking patients history for reasons that would cause densely adherent lung to the chest wall throughout the hemithorax.2

Fatal outcome after chest drain error

Mrs A, was admitted for a triple coronary artery bypass graft operation for her NSTEMI. She had a past medical history of thoracic (T9-T10) spinal fusion for fractures secondary to a viral illness more than 20 years ago. Her cardiac surgery went ahead as planned with no apparent complications. Two weeks later she re-presented to the cardiothoracic surgeons with shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her readmission bloods (full blood count and urea and electrolytes) were within the normal ranges.

Mrs A, was admitted for a triple coronary artery bypass graft operation for her NSTEMI. She had a past medical history of thoracic (T9-T10) spinal fusion for fractures secondary to a viral illness more than 20 years ago. Her cardiac surgery went ahead as planned with no apparent complications. Two weeks later she re-presented to the cardiothoracic surgeons with shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her readmission bloods (full blood count and urea and electrolytes) were within the normal ranges.

She was then given a therapeutic dose of heparin for the likelihood of a pulmonary embolus (see Figure 1). Later that day, a CT pulmonary angiogram revealed that she had pleural and pericardial effusions, a partially collapsed right lower lobe and no pulmonary embolus. The area for pleural fluid drainage was marked on the right side of her chest under ultrasound in the Radiology department (see Figure 2).

She was then given a therapeutic dose of heparin for the likelihood of a pulmonary embolus (see Figure 1). Later that day, a CT pulmonary angiogram revealed that she had pleural and pericardial effusions, a partially collapsed right lower lobe and no pulmonary embolus. The area for pleural fluid drainage was marked on the right side of her chest under ultrasound in the Radiology department (see Figure 2).

While on the wards, Mrs A’s respiratory system started to compromise and an urgent chest drain was inserted with a blunt dissection technique by an experienced surgeon, Mr B. During the procedure, Mr B felt thin fibrous strands on finger sweeping of the chest cavity. These were thought to be adhesions within the chest cavity post cardiac surgery.

While on the wards, Mrs A’s respiratory system started to compromise and an urgent chest drain was inserted with a blunt dissection technique by an experienced surgeon, Mr B. During the procedure, Mr B felt thin fibrous strands on finger sweeping of the chest cavity. These were thought to be adhesions within the chest cavity post cardiac surgery.

The strands were separated by the surgeon’s finger with ease and the chest drain was inserted with no resistance. The chest X-ray that was taken after the chest drain insertion demonstrated the intercostal drain to be in the patient’s abdomen (see Figure 3).

Shortly afterwards, Mrs A became haemodynamically unstable with severe haemorrhaging from the drain site, before arresting. She was resuscitated in the Cardiothoracics Intensive Care Unit and was brought into theatre.

Shortly afterwards, Mrs A became haemodynamically unstable with severe haemorrhaging from the drain site, before arresting. She was resuscitated in the Cardiothoracics Intensive Care Unit and was brought into theatre.

A laparotomy revealed a lacerated diaphragm and traumatic injury to segment 5/6 of the liver. The haemorrhagic points were packed and the chest drain was withdrawn a few centimetres to be repositioned in the chest cavity (see Figure 4).

In the days that followed Mrs A developed multi-organ failure and continuous veno-venous haemofiltration had to be commenced. Her sedatives were stopped temporarily, but she did not regain consciousness.

In the days that followed Mrs A developed multi-organ failure and continuous veno-venous haemofiltration had to be commenced. Her sedatives were stopped temporarily, but she did not regain consciousness.

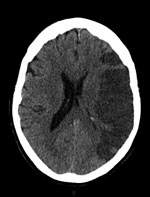

A CT scan of her brain four days after the laparotomy showed a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarct (see Figure 5). Her prognosis was discussed with her family and they were in agreement for treatment to be withdrawn the next day. The patient passed away peacefully a day after treatment was stopped. This case highlights the importance of a patient’s past medical history on initial assessment, even when it is seemingly unrelated to the proposed procedure.

What went wrong?

Mrs A’s past medical history of spinal fusion surgery for thoracic vertebrae nine-ten fractures, played a role in altering her thoracic anatomy and misplacing the chest tube, which led to her devastating outcome.

This case is interesting because there is no similar literature or reports about the implications of spinal surgery on the insertion of chest drains found in PubMed, MEDLINE or EMBASE databases. Mr B, an experienced surgeon, inserted the chest drain; he had not had any previous complications in any of the 500 chest drains he had inserted before. The texture of Mrs A’s diaphragm indicated that it was easily friable, fibrosed and most likely had tented upwards into the chest cavity.

The adhesions assumed to be between the chest wall and the lung during the procedure were proven not to be the case; rather they were adhesions between the chest wall and the diaphragm, and between the liver and diaphragm. It is also believed that the tip of the chest drain did not cause the liver haemorrhage, but rather it was the sheering of the adhesions from the liver surface that did so.

Would there have been less haemorrhage and Mrs A’s death prevented, if she had not received any empirical therapeutic heparin prior to a CT pulmonary angiogram?

If the patient hadn’t needed an urgent chest drain, would a coagulation screen prior to the procedure have detected any coagulopathy?

Also, if the patient’s past medical history had been given more consideration, would the chest drain insertion have been carried out under ultrasound guidance throughout the whole procedure?

Taking into account that the success rates of image guided chest tube insertion has been reported to be only 71-86%, would real time imaging during the procedure have prevented this tragedy?3

Miss Th’ng is an SHO and Mr Patronis is a cardiothoracics SPR.

MPS Advice

MPS medicolegal adviser Dr Gordon McDavid comments on the case

This tragic case highlights the risks involved in all medical procedures – even those carried out relatively frequently. It offers a stark reminder of how challenging medicine can be – diagnostic uncertainty often requires doctors to consider the most likely and most significant diagnosis, which may later turn out to be incorrect; in this case the presumed PE.

Fortunately, chest drain complications are rare. However, it is important that care is taken before any procedure to ensure the patient has provided their informed consent and that conditions are as safe as possible. If there is any doubt, the procedure should be postponed until you have investigated further; provided it is clinically appropriate to do so.

In this case, the patient required a chest drain as an emergency which meant that the usual careful preprocedure consideration could not be undertaken. A doctor would be expected to act in a patient’s best interests at all times. Action should be taken to save their life or prevent serious deterioration in a patient’s condition.

When an adverse event occurs, investigations will follow. It is vital that meticulous notes are made contemporaneously. This will assist the doctor by explaining what happened at the time and offering justification for the steps taken.

The surgeon who carried out the chest drain insertion will undoubtedly feel terrible about what happened. It is important to remember that mistakes do happen. The most important step following any adverse event is to ensure the patient is looked after.

When suitable, the patient should be informed openly about what happened – in this case, as the patient did not recover, that explanation should be offered to the family in an honest and considerate way.

An adverse event should be formally reported so that it can be thoroughly investigated to consider if any steps should be taken to prevent recurrence. The individuals involved should participate in that process fully, but see it as a learning exercise, rather than a process to attribute blame.

Those involved should also undertake personal reflection no matter how senior they are. Discussion with colleagues is also helpful, to consider what they would have done in similar circumstances. Any adverse event should be discussed at the doctor’s appraisal too. In conjunction with the hospital’s internal review, there may be other processes that arise out of an adverse event.

Where a patient has died, it is likely the case will be considered by the coroner or procurator fiscal who may call an inquest or fatal accident inquiry. To assist in such investigations, a professional report will be sought from those involved. Therefore it is useful for a doctor to compose a draft report as soon as possible after an adverse event.

Remember that MPS remains on hand for members to contact for advice. Offering more than just defence, we can assist in annotating a professional report and offer guidance, advice and support through the multiple processes that may arise out of a clinical incident.

When things go wrong, a complaint from the family may follow – either directly to the hospital or through other channels, such as the GMC. They may also attempt to claim for damages. You can contact MPS for advice if such developments transpire.

Download a PDF of this edition