Fatal outcome after chest drain error

Post date: 14/11/2022 | Time to read article: 2 minsThe information within this article was correct at the time of publishing. Last updated 14/11/2022

Mrs A, was admitted for a triple coronary artery bypass graft operation for her NSTEMI. She had a past medical history of thoracic (T9-T10) spinal fusion for fractures secondary to a viral illness more than 20 years ago. Her cardiac surgery went ahead as planned with no apparent complications. Two weeks later she re-presented to the cardiothoracic surgeons with shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her readmission bloods (full blood count and urea and electrolytes) were within the normal ranges.

Mrs A, was admitted for a triple coronary artery bypass graft operation for her NSTEMI. She had a past medical history of thoracic (T9-T10) spinal fusion for fractures secondary to a viral illness more than 20 years ago. Her cardiac surgery went ahead as planned with no apparent complications. Two weeks later she re-presented to the cardiothoracic surgeons with shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her readmission bloods (full blood count and urea and electrolytes) were within the normal ranges.

She was then given a therapeutic dose of heparin for the likelihood of a pulmonary embolus (see Figure 1). Later that day, a CT pulmonary angiogram revealed that she had pleural and pericardial effusions, a partially collapsed right lower lobe and no pulmonary embolus. The area for pleural fluid drainage was marked on the right side of her chest under ultrasound in the Radiology department (see Figure 2).

She was then given a therapeutic dose of heparin for the likelihood of a pulmonary embolus (see Figure 1). Later that day, a CT pulmonary angiogram revealed that she had pleural and pericardial effusions, a partially collapsed right lower lobe and no pulmonary embolus. The area for pleural fluid drainage was marked on the right side of her chest under ultrasound in the Radiology department (see Figure 2).

While on the wards, Mrs A’s respiratory system started to compromise and an urgent chest drain was inserted with a blunt dissection technique by an experienced surgeon, Mr B. During the procedure, Mr B felt thin fibrous strands on finger sweeping of the chest cavity. These were thought to be adhesions within the chest cavity post cardiac surgery.

While on the wards, Mrs A’s respiratory system started to compromise and an urgent chest drain was inserted with a blunt dissection technique by an experienced surgeon, Mr B. During the procedure, Mr B felt thin fibrous strands on finger sweeping of the chest cavity. These were thought to be adhesions within the chest cavity post cardiac surgery.

The strands were separated by the surgeon’s finger with ease and the chest drain was inserted with no resistance. The chest X-ray that was taken after the chest drain insertion demonstrated the intercostal drain to be in the patient’s abdomen (see Figure 3).

Shortly afterwards, Mrs A became haemodynamically unstable with severe haemorrhaging from the drain site, before arresting. She was resuscitated in the Cardiothoracics Intensive Care Unit and was brought into theatre.

Shortly afterwards, Mrs A became haemodynamically unstable with severe haemorrhaging from the drain site, before arresting. She was resuscitated in the Cardiothoracics Intensive Care Unit and was brought into theatre.

A laparotomy revealed a lacerated diaphragm and traumatic injury to segment 5/6 of the liver. The haemorrhagic points were packed and the chest drain was withdrawn a few centimetres to be repositioned in the chest cavity (see Figure 4).

In the days that followed Mrs A developed multi-organ failure and continuous veno-venous haemofiltration had to be commenced. Her sedatives were stopped temporarily, but she did not regain consciousness.

In the days that followed Mrs A developed multi-organ failure and continuous veno-venous haemofiltration had to be commenced. Her sedatives were stopped temporarily, but she did not regain consciousness.

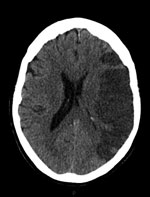

A CT scan of her brain four days after the laparotomy showed a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarct (see Figure 5). Her prognosis was discussed with her family and they were in agreement for treatment to be withdrawn the next day. The patient passed away peacefully a day after treatment was stopped. This case highlights the importance of a patient’s past medical history on initial assessment, even when it is seemingly unrelated to the proposed procedure.